Catalogues

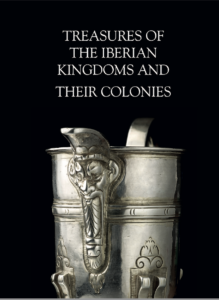

Treasures Of The Iberian Kingdoms And Their Colonies

Click here to view the catalogue…

The Age of Discovery, or of Exploration as it is sometimes called, describes the period starting in the 1400s through to the 17th century during which European seafarers headed out into the Atlantic to explore hitherto unknown lands and sea routes. At the forefront were the kingdoms of Portugal and Spain. The Dutch, English and French followed on soon afterwards. The colonization by Europeans which followed their discoveries led to the establishment of global trade networks bringing massive wealth back to Europe and adding financial ‘fuel’ to the Renaissance.

Several factors were involved. Advances in ship design and in navigational equipment enabled the undertaking of long ocean voyages with ships capable of withstanding the ferocious conditions involved. Gunpowder and more sophisticated armaments enabled these ships and their crews to defend themselves against any hostilities they might encounter. Thus, the royal houses of Europe became interested in sponsoring such voyages in the hope of bringing themselves greater wealth and prestige.

Above all, there was a pressing commercial need to find a sea route to the East Indies. For centuries Europe had relied on overland routes, the so called ‘silk roads’, for the transportation of valuable and exotic goods, such as spices, silk, gold and precious stones, from the east. However, by the 1400s these routes had become increasingly unreliable. The Mongolian empire which had protected these routes was breaking up and in the eastern Mediterranean trade was controlled by the Ottomans and the Venetians.

Starting in 1418 the Portuguese began systematically exploring the west coast of Africa under the sponsorship of Infante Dom Henrique. In 1488 Bartholomew Dias rounded southern Africa thereby reaching the Indian Ocean by this route.

In 1492 Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus, sponsored by Spain, made the first journey heading directly west across the Atlantic

making landfall in the West Indies. In his fifth and final journey he explored some of the coast of Central America. Columbus thought that he had reached the Spice Islands of the east, but it later became apparent that a whole new continent had been discovered. Throughout this period a series of Treaties were made between Portugal and Spain, often with intervention from the Pope, to divide control of these new discoveries between the two countries. The Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 basically gave exclusivity to Portugal of Africa, Asia and Brazil; the remainder of South and Central America to Spain.

In 1498 a Portuguese expedition led by Vasco da Gama reached India by sailing round Africa so opening up a direct trade route between Europe and Asia bypassing the old overland routes. In subsequent journeys the Portuguese continued to press further eastward, reaching the Spice Islands in 1512 and landing in China a year later. They did not arrive in Japan until 1543. The first circumnavigation of the world was completed in 1522. In 1519 a fleet of five Spanish ships left Seville under the command of Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan. Arriving in the Philippines in 1521, Magellan claimed these for Spain, but he himself was killed in a local skirmish. Of the two remaining ships one headed back east and was promptly captured by the Portuguese. The other, the Victoria under the command of Spaniard Juan Sebastian Elcano continued heading westward, eventually arriving back in Seville on the 6th September 1522.

In the following years, meetings were held between Spain and Portugal to try and determine the exact location of the anti meridian on which the Treaty of Tordesillas had been based, but no precise calculation proved possible as a result of lack of knowledge at the time. However the Treaty of Zaragoza signed in 1529 attributed the Moluccas ( the Spice Islands ) to Portugal and the Philippines to Spain.

The approach of the two nations to the colonization of their territories was quite different. In Asia, the Portuguese relied on naval power to protect their new trade routes by establishing a series of heavily fortified ports, notably at Ormuz and at Goa. In the Americas, the Spanish were faced with exploring hitherto unknown lands. Spurred on by stories of untold riches, they mounted armed inland expeditions. In February 1519 a band of ‘conquistadors’ led by Hernan Cortez overthrew the Aztec empire in Central America. Their capital Tenochtitlan was later renamed Mexico City and became the administrative centre of ‘Nueva Espana’. Following the Treaty of Zaragoza, the Spanish quickly established a trade route across the Pacific from the Philippines to Mexico.

In 1522, Francisco Pizzaro accompanied by his brother and some 168 Spanish soldiers overthrew the Inca empire in Peru. Three years later Pizzaro founded Lima as the capital of this new Spanish Viceroyalty. In nearby Bolivia, huge deposits of silver were discovered in the Potosi mountains. It is estimated that between the 16th and 18th centuries approximately 80% of the world’s silver supply came from these mines. Carried overland to the Pacific coast, the silver continued its journey by ship to Panama, then transported across the isthmus to the Caribbean coast to be reloaded once more on to ships for Europe. All this new wealth arriving into Iberia then flowed in part to Northern Italy and Southern Germany, whose banking families had provided finance for many of the earlier voyages of discovery.

In both Asia and the Americas local workshops were set to work producing goods for export to Europe and made in the European taste. However, being made with local materials and techniques, for example lacquering which was unknow in Europe, these pieces have a very distinctive character. There are several examples of such pieces within this Catalogue.

Clearly inquisitiveness and commercial opportunity were major factors driving the Age of Discovery. However religious zeal played an equal role. A motivation for Dom Henrique in sponsoring the early Portuguese explorations of Africa was to discover how far south Islamic influence had spread. For the conquistadors the spread of Christianity was an integral part and justification for the conquest of new lands. To assist with conversion to Christianity religious objects were produced in local workshops as visual aids to illustrate the teachings of the bible.

The various Treaties made between Spain and Portugal maintained some reasonable order between them in the establishment and management of their colonies. Between 1580 and 1640 both nations fell under one rule, but it was agreed that their respective colonies should remain separately governed. The problem for the Iberian kingdoms was that the Dutch, English and French were not bound by any such Treaties, so over time colonies were lost to these other nations. However, the social, religious, political and commercial geography created in Asia, Africa and the Americas during the Age of Discovery still resonates loudly in the world of today.

An Important Charles I Period Verge Watch London c.1640; the maker David Bouquet I

Click here to view the catalogue…

Oval gilt-brass pre-spring verge movement with engraved pillars, gut line fusee and worm and wheel set up; oval dial set with octagonal gold mount decorated with enamel tulips

and butterflies amongst leaves in colours of blue, green and orange, all against a white background.

The circular gold chapter ring with black enamel Roman numerals centred by a gilt floriatehand, the inner border to cover and case decorated with green and blue enamels over an

engraved ground, the case of faceted rock crystal in engraved and gilt-brass mounts, the bezels and pendant also with green and blue enamels.

Very few watches of this period have survived, and of those that have, most have had their original movement removed or replaced by a later one – see for example the one

illustrated in Terence Camerer Cuss, The English Watch 1585 – 1970, 2009, pp 60-61, pl 23.In that example the movement is a later 18th century replacement, but otherwise the age,

design and decoration of that piece are very similar to the present example and may well be by the same maker.

Given the age and delicacy of the piece it is in remarkable condition. There are some minor losses to the enamels and the rock crystal case has had a couple of knocks where it has been called upon to protect the contents inside. The small delicate nature of this piece and its intricate decoration suggests, we believe, that it was made for a high status lady.

It would have been worn on a chain hung round the neck – see the picture in the Royal Collection of a young Lord Darnley (the father to be of James I) which shows him wearing a watch in this fashion (RCIN 403432). At this stage in the early development of watches, it would not have been particularly efficient. It would have needed to be wound twice a day; it would have maintained accuracy to within about ten minutes.

The maker David Bouquet I is noted in Brian Loomes, Clockmakers of Britain 1282 – 1700 Mayfield Books, Ashbourne, 2014 at p.63. By the beginning of the 17th century there were a number of foreign clock and watchmakers working just outside the control of the City of London, particularly in the area of Blackfriars, one of the so-called “liberties”. Many of these ‘strangers’ were Hugeunot refugees from France who were particularly skilled in the art of engraving, enamelling and lapidary work.

Their existance so near the City had a significant impact on the established clock and watchmaking trade. In 1622 a Petition was raised by a group of watchmakers in the Blacksmith’s Company and was sent to King James I in an attempt to prevent them trading and requesting the establishment of a Livery Company for the Clock and Watchmakers of London.

The first record of David Bouquet is in this Petition where he is referred to as ‘David Bowkett at Mr. Samsom’s house with two apprentices’ (presumably Sampson Shelton, a member of the Blacksmith’s Company) and living in Blackfriars.

Bouquet became a Freeman of the Blacksmith’s Company in June 1628, and subscribed an unspecified sum towards the incorporation of the Clockmaker’s Company in 1630 (as Mr Bucket) later being made a Free Brother of that Company in 1632 and in which he became Assistant from 1634 to his death in 1665. Bouquet was a prominent member of the Huguenot church and served as a warden at the French Church in Threadneedle Street for four periods of three years each between 1637 and 1662. He had three sons. David and Solomon, who both became watchmakers, and Hector who was apprenticed to the diamond cutter Isaac Merbert. Bouquet continued to run a prolific workshop in Blackfriars with

mumerous apprentices until his death.

Bouquet’s work, some signed ‘D. Bouquett, London’, ‘David Bouquet a Londres’, or ‘D. Bouquet A Londres’ was mainly watches, but lantern clocks by him are known. A tiny lantern clock in a silver case, now with verge pendulum, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum. There are notable watches by Bouquet in the British Museum, the British Royal Collection, the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

Provenance:

Anonymous Sale, Peter Ineichen Auction, Zurich, after 1973;

With Fred Kats, Rotterdam;

Private collection, Netherlands,1978 – 2012, thence by descent.

Literature:

Reinhard Meis, Taschen Uhren, Vonm der Halsuhr zum Tourbillion, Callway Verlag,

Munchen, 1999, 5th edition, p. 84,pl 57-58 where this piece is illustrated.

Dimensions:

Length including pendant 46mm, width 24mm

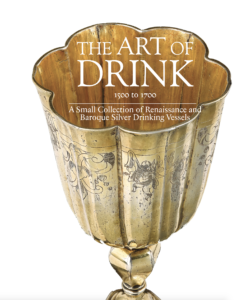

The Art Of Drink

A Small Collection of Renaissance and Baroque Silver Drinking Vessels

“Beauty perishes in life, but is immortal in art” – Leonardo da Vinci

The connection between art and the fragility of life to which Da Vinci is referring may explain why from the very earliest of times, the makers of drinking cups and related vessels instinctively decorated them. By the Renaissance period, their craftsmanship had reached a level of refinement that such items almost ceased to be functional and came to be regarded as art objects. The status of their creators was elevated from artisans to artists.

The sharing of drink is an act of friendship and of community. Some types of drinking vessels, such as Bernegals and Bratina, were designed specifically for the purpose of their contents being shared.

The use of silver in drinking culture also dates back to the earliest of times. Its antibacterial quality was recognized and, being a relatively easy material to work, made it ideal for the purpose. Whilst the more substantial and magnificent pieces were the domain of the elite, smaller vessels such as beakers were more easily within the budget of modest families.

With the aim of illustrating these points, we present a small collection of various types and styles of silver drinking vessels from the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

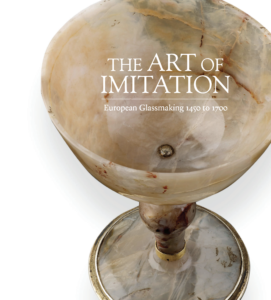

The Art of Imitation – European Glassmaking 1450 to 1700

European Glassmaking 1450 to 1700

In the forward to his book L’Arte Vetraria, first published in 1612, the Florentine priest and alchemist Antonio Neri discusses the nature of glass. Whilst accepting that it is akin to naturally formed rocks and minerals, he concludes that it is “a compound, and made of art”. In the ensuing Chapters of the book, he describes in extraordinary detail recipes and techniques for making glass of different colours and types. The beauty of such glasses, he describes “it will be seen as if nature herself could not arrive to the like perfection, nor art imitate it”.

Neri himself worked as a glassmaker in Florence under the patronage of Don Antonio de Medici, to whom the book is dedicated. He is also known to have worked in Pisa and in Antwerp. Far from being academic, therefore, the descriptions he gives are of a very clear and practical nature. He often invites his reader that if he follows his recipes precisely, then an immediately perfect result will be achieved.

Special Sales

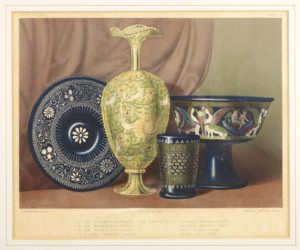

A highly important Venetian enamelled and gilt blue-tinted standing bowl.

Late 15th century.

Of rounded form and folded rim, painted with pairs of winged sphinxes opposing a cherub’s head emerging from a vase alternating with pairs of cherubs seated on gilt urns, on a grassy sword and reserved on a ground of gilt scrolling foliage, below a gilt inscribed ‘TENPORE FELICI MVLTI NOMINANTVR AMICI’ over a high trumpet foot with folded rim brushed with gilding.

16.5cm high by 20.8cm diameter.

Provenance.

George Field

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905) Paris

Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949) Paris

Baron Batsheva de Rothschild (1914-1999) Tel Aviv

Rothschild Inv.nos.P48 and E de R 261(?)

Exhibited

The Art Treasures of the United King- dom. Manchester,1857

Illustrated by J.B Waring, Catalogue of the Art. Treasures of the United Kingdom collected at Manchester in 1857, in the section headed ‘The Museum of Ornamental Art’, London (1858), Chromolithograph, pl.2

The inscription translates as ‘In times of abundance one has lots of friends’

The sphinx motif appears on a green beaker attributed to Venice,circa 1500, formerly in the Kunstgewerbe Museum,Berlin(see R Schmidt, Das Glass,Berlin,p.93,p156 and F.A.Dreier, ‘Ein venezianischer Emailglas- Pokal,Aus der Sammlung Lady Bagot’ Kunst & Antiquitaten, zeitschrift fur Kunstfreunde Sammler and Museen,Heft 111’ 1986’p56 pl 5. Although the beaker was probably destroyed during the Second World War Schmidt describes it, op cit, as decorated with sphinxes, cherub’s heads and putti. The putti on the present example bear a close resemblance to those on a blue-tinted standing bowl in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio (ex collections Charles Stein,Paris, and Maurice de Rothschild ,Geneva) (see R.Barovier-Mentasti et al,exhibition catalogue, Mille anni Di rate del vetro a Venezia, 1982, p81. Nos 71ac, and R.von Strasse and W. Spiel,Dekoriertes Glas,1989,p28.pl 27)

No other blue-tinted Venetian standing bowl with a gilt band etched with an inscription is recorded in the literature. a part-coloured shallow bowl,however, in the Museo Ala Ponzone, Cromona, with a partial gilt amethyst-tinted trumpet-shaped foot,is also inscribed within a gilt border below the rim. This example was recorded in the museum’s collection at least as early as 1840 (see R.Barovier Mentasti et al.Les Gaes du Verre,p 176, no 51). Similar inscriptions also appear on five clear glass bowls from the late 15th century . See the example exhibited in the Museen Ariana, Geneva,1995 (illustrated Erwin Baumbgartner, Verre de Venise, pp31 and 91, 172)

One in the Victora and Albert Museum (see W.B Honey, handbook of the Collections,1964,p132C), another in the British. Museum, London (see Hugh. Tait The Golden Age of Venetian. Glass,1979, p.38, no 28) a fourth in the Wurttembergisches Landesmuseum, Stuttgart (formerly in the Ernesto Wolf Collection,see B.Klesse, European Glass from 155-1800. No 8) and another in the Louvre Museum, Paris (Inv 0A1119). Four of the bowls mentioned engraved in capital letters in the ‘antique’ on a gilt band applied to the exterior.

George W. Field was born on the 13th November 1798 and lived at Ashurst. Park, a large house Set in its own grounds close to Tunbridge Wells,Kent. When he assembled his art collection Is unrecorded but Field appears to have been well-known as a collector of Renaissance and Mediaeval art to some of the leading connoisseurs of the day. On 17th September 1856 he was invited to lend items to the exhibition of the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom to be held in Manchester in 1857. the criteria for the choice of exhibits were largely based on the wide personal knowledge of British private collections by the noted German art historian Gustav Waagen. Amongst the numerous items inspected by J.B.Waring,the organiser of the Works of Art Section,the present lot was selected for display. Further 16th century items, including ivories, bronzes and wood carvings were also selected. From the extensive list of exhibits found in the City of Manchester archives, Field’s collection was both eclectic and diverse (M6/2/21) they included ‘Queen Elizabeth’s Prayer’. Book,silver gilt and enamelled, very rare and fine work’ (P206), ‘A very fine crystal cup formerly part of the Crown Jewels of France,lately the property of Louis Phillips’ 2 carved ebony chairs from Strawberry Hill’ (p140) and some fine Dutch 17th century oil paintings by several of the leading masters (M6/2/32). Of the glass that was returned to him after the closure of the exhibition ‘1 opal cup,1 Venetian bowl, blue and finely enamelled ,3 cups of Ruby glass and 2 Venetian glass vases mounted’ are recorded. In the introduction to the section of the exhibition catalogue devoted to ‘the. Museum of Ornamental Art’ Waring acknowledged the contribu- tions of Earl Cadogan,Lord de Tabley,Mr Field and the Duke of Buc- cleuch, as ‘amongst the most remarkable examples’ (Catalogue, 1857, p149) field’s glass was exhibited alongside that lent by Felix Slade who subsequently donated his extensive collection to the British Museum.

Blue-tinted glasses and especially footed bowls of this type are well known in the corpus of Venetian production of the 15th and early 16th.centuries.Indeed, Henry V111 of England is known to have had standing Cuppes of blewe glasses wt covers to they’d painted and uilte’ (See D Battle and S Cottle,Sotherby’s Concise encyclopaedia of. Glass,p60). In shape and form one of the closest related examples to the present lot is the famous blue glass mar- riage bowl, commonly known as ‘The Angelou. Barovier Cup’ ( In the Museo Vetrario, mutant- see Barovier(1982) p74-78,no 70. Angelo Barovier was until recently credited with the fine enamel decoration. he was widely praised as one ‘who knew the whole of the art of glass’ and had won the respect of Alphonse,King of Naples, the. French court and the. Duke of Milan. The Barovier Cup is however, now thought to date from 1470-1480’ some ten years after Angelo’s death in 1460.

As Hugh Tait has commented,almost nothing is know about the Venetians who decorated these chefs-d’ouuvres of the Renaissance and not one single glass can be identified as the work of a particular artist.

As Hugh Tait has commented,almost nothing is know about the Venetians who decorated these chefs-d’ouuvres of the Renaissance and not one single glass can be identified as the work of a particular artist.

In recent years the dating of Venetian enamelled and gilt blue-tinted glass has been assisted by excavations of burial mounds in the Russian Caucasus, an area originally under the control of the Mongul khans of the Golden Horde (1226-1502), the archaeological evidence indicates that such glass was produced in Venice and traded via Italian colonies established along the Silk Route in the 14th and 15th centuries.They include complete examples of purple/green and blue glass decorated with scale and dot and lozenge and flower ornament typical of much of the existing material ( see the article by Mark Kramarovsky).’the import and manufacture of glass in the territories of the. Golden Horde’ published by Rachel Ward (ed) Gilded and Enamelled Glass form the Middle East,British Museum,1998’pp96-100). Kramarovsky, a curator at the Hermitage Museum,St. Petersburg,refers to several coloured Venetian glass from the excavations now in the Museum’s collection including a blue glass tankard(fig 22.5) decorated in enamels and gilding with flowers in diamond-shaped frames,found in Digoria ( Northern Ossetia ,Caucasus).

For similar figurative decoration,The Weoley Cup, a late 15th century.

Venetian clear glass goblet, has a provenance as early as 1547.Presented to the Worshipful Company of Founders in London by its Master, Richard Weoley, in 1642-43, this goblet is crucial in the early dating of such glass. According to Weoley,he had purchased the cup from a family whose ancestors had brought it back from Boulogne at the time it surrendered to Henry V111 in 1546. This story is given credibility through the London hallmarks on the silver gilt foot,which can be dated to 1547 and thus provide the glass with an exceptionally early provenance(see the exhibition catalogue, gothic: Art for. England 1400-1547, Victoria and Albert. Museum,2003 p208.

Another glass gilded and enamelled vessel with provenance is the famous Fairfax cup,preserved in the V and A museum in its original bag from the 17th century, but dating from the late 15th century.

The date of the acquisition by the Rothschilds of this bowl for their famed collection of Venetian and Islamic enamelled glass is unknown, Nonetheless,it may not be entirely coincidental that. Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905) married his English cousin Leonora in 1857.Her uncle. Sir Anthony Rothschild was a major contributor to the Manchester Art. Treasures exhibition in that same year, and may have come into contact with George. Field. It is possible that Alphonse and Leonora visited the exhibition.

X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis of an Enamelled Glass Bowl, Venice, Circa 1490

1st June 2015

Dr. K. Domoney Professor A.J. Shortland

Centre for Archaeological and Forensic Analysis Cranfield University, Shrivenham, Oxon SN6 8LA

Conclusion

The analysis of the glass and enamels have produced some clear patterns is terms of flux and colorant identification. Results are consistent with previous analytical data from collections of Renaissance Venetian glass and with traditional Renaissance Venetian glass recipes dating to the 15th and early 16th centuries. Evidence of later pigments and opacifiers such as chromium green, calcium antimonite and lead arsenate were not found.